The photographer we’re photographing is a bit like a “water sprinkler”, that is, a person who suffers the same fate that he inflicted on others.

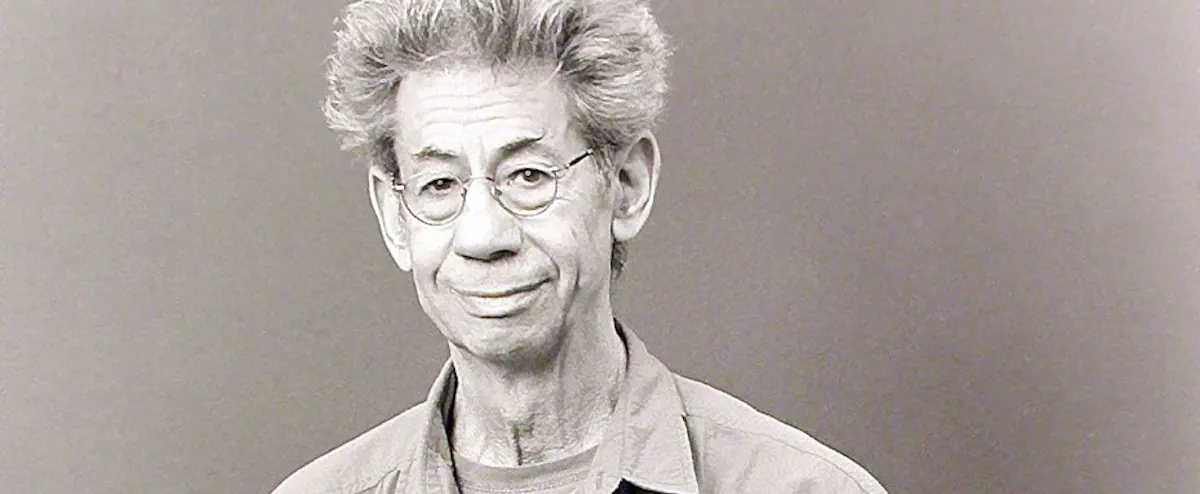

Pointing the camera at Gabor Zelassi, young director Joan Lavrinier, herself a photographer, only repeated what the famous Montreal photographer of Hungarian descent allowed thousands and thousands of people. More than 80,000 negatives of all the ordinary Quebecers he photographed are now certain of eternal life in the vaults of Canadian library and archives.

Even if this man whom everyone calls by his first name Gabor is at the end of an unforgettable career as that of Henri Cartier-Bresson, one of the most famous photographers in history, very few know him, even if most of them could. Let’s see from his picture. I met Gabor several times, a long time ago, when he was doing his job at the Quebec Film Bureau. Hundreds of photography students at Cégep du Vieux Montréal and the University of Concordia will remember this warm and chatty longtime professor, who still marvels after so many years of magic taking place in a darkroom.

Gabor falls in love

Like well-known film producers Robert Lantos and Andrej Link, Gabor fled Hungary in 1956 when the communist government ruthlessly crushed the citizens’ revolt. Slightly older than his Hungarian compatriots Lantos and Link, Gabor first tried to flee Budapest in 1949, but was caught and thrown into prison. After a short stay in Paris, Gabor settled in Montreal. As Michel Braault and Pierre Perrault (film directors for the rest of the world), fell in love with the people of Ile-aux-Coudres, Charlevois and the Pas du Fleuve. Gabor photographed them from all angles.

Joanne Lavrinier’s documentary constantly shows the hero with his camera glued to his eye as if it were a monocular or an eye patch. One of the best things about the movie is to bring the color image that Gabor just froze in his camera to the big screen in black and white. This stunt has the advantage of making us see that once framed by a brilliant photographer, a scene that looked ordinary even in color turned out to be exceptional in black and white.

Part of our history

Joannie’s film, which has already toured at several festivals, including Toronto’s Hot Docs, Atlanta Film Festival and Vues sur mer de Gaspé, where it has received special mention, will be shown tomorrow evening (Friday) at the Cinéma Beaubien. It will then be presented at the Cinéma Le Clap in Sainte-Foy, and then at the Maison du Cinéma in Sherbrooke.

The documentary often shows Gabor thinking out loud. Photography is a poem and cinema is a novel!

If I had to paraphrase Gabor, I’d rather say Joan Lavennier’s film is a “river novel.” His film lasts 1 hour and 41 minutes, and is often repeated and continued. The director would do well to go some distance and see him again. She would undoubtedly discover that she had let herself be carried away by the undeniable benevolence and apparent humanity of this exceptional photographer whose photographs are such an integral part of our history. “My father and daughter Andrea rightly say, it is just creativity and love! »

“Total creator. Evil zombie fan. Food evangelist. Alcohol practitioner. Web aficionado. Passionate beer advocate.”