(Paris) This sum is astronomical and makes sense when it comes to Albert Einstein: A manuscript in which the famous physicist prepared his theory of general relativity was auctioned for a record 11.6 million euros (16.5 million Canadian dollars), Tuesday in Paris.

Jean Francois Guyot and Paul Ricard

France media agency

Previous records for Einstein’s manuscript were $2.8 million ($3.4 million Canadian) in 2018 in New York City for a letter to God, and $1.56 million ($1.98 million Canadian) in 2017 in Jerusalem for a message about the secret of happiness.

The document, estimated to be worth between two and three million euros, was sold on Tuesday for 11.6 million euros in costs (14.5 million Canadian dollars). Unlike the one that broke the previous two records, it is a scientific working document, which makes it a rarity.

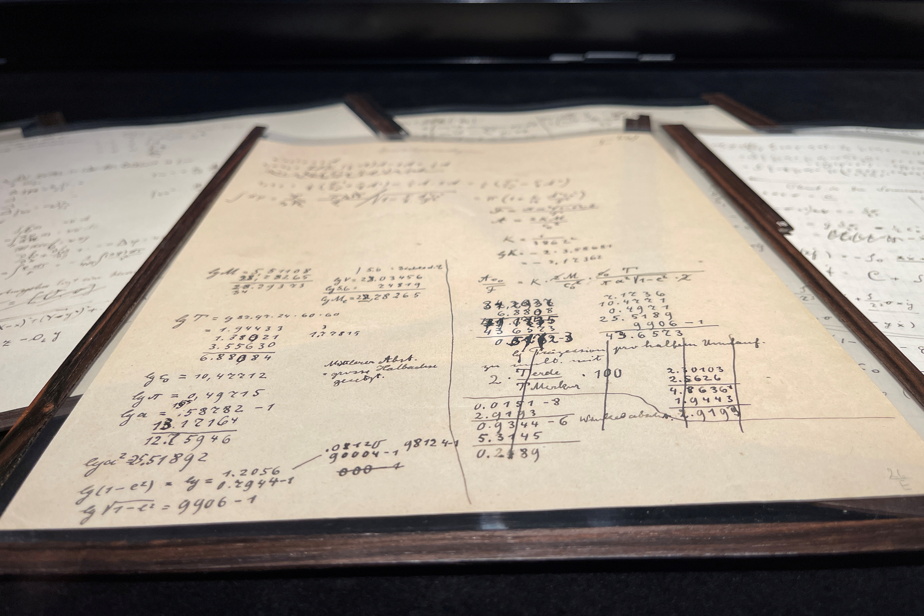

It is a 54-page signature manuscript written in 1913 and 1914, in Zurich (Switzerland), by German-born physicist, collaborator and confidant Michel Besseau.

“Documents of Einstein’s scientific signatures from this period, and in general from before 1919, are extremely rare,” he had emphasized before the sale of Christie’s, where the Agotis house was auctioned.

These started at 1.5 million (2.1 million) and flew in a few minutes, and ended with a fight between two buyers over the phone in increments of $285,000.

The nationality of the buyer was not known at the beginning of the evening. A hundred curious and collectors were present in the room, and none of them were bidders.

Genie and Pop character

According to Christie, it is to Besso’s credit that “the manuscript reached us, almost miraculously: Einstein probably would not have bothered to keep what seemed to him to be a working document.”

After his theory of special relativity, which had him demonstrating in 1905 the famous formula E = mc², Einstein began work on general relativity.

This theory of gravity, finally published in November 1915, revolutionized our understanding of the universe. Einstein died in 1955 at the age of 76, and became as much a symbol of scientific genius as he became a popular figure, with the famous 1951 photograph where his tongue sticks out.

In early 1913, he and Besso addressed “one of the problems the scientific community has faced for decades: anomalies in the orbit of Mercury,” Christie’s recalls. The two worlds will solve this puzzle.

Not in the false accounts on this manuscript, which counts “a certain number of errors that have gone unnoticed.” When Einstein discovered them, he was no longer interested in this manuscript that Besso had taken.

“For being one of only two working manuscripts documenting the genesis of general relativity that has survived, it is an extraordinary testament to Einstein’s work and allows us to plunge into the mind of the greatest scientists of the 20th century,” according to Christie.

The other known document from this crucial period in the physicist’s research, known as the “Zurich Notebook” (late 1912, early 1913), is actually kept in the Einstein Archives of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.