magazine. As far as he can remember, Jeffrey Gallant was a lover of science and adventure. Now a world-renowned explorer, scuba-diving specialist and shark defender thinks highly of his research group.

During his youth in Drummondville, Jeffrey Gallant enjoyed every episode of the TV series starring captain Jacques-Yves Cousteau. The legendary French explorer soon became a huge inspiration to him.

“I really liked it when he went on an expedition and told me what he saw,” Gallant said. It’s always fascinated me. I’ve started doing the same thing as Cousteau, but on a small scale. Almost every day, we would go fishing with friends at Hemming Dam. I soon gave up hunting to take care of the animals.”

At the same time, young Galant is passionate about diving. Through Sea Cadets, he trained in British Columbia. “From there it was love at first sight! I Never Stopped Diving,” recalls the bestselling author Diving calendar and record book.

In 1996, Jeffrey Gallant began developing a passion for sharks, when his path crossed the path of researchers Aidan Martin and Chris Harvey Clark during a conference in Nova Scotia. “Chris had seen the headlines saying sharks had been caught in Saguenay Gorge, under the ice. Aidan asked me why I shouldn’t go and investigate.”

During diving trips, Galant stops in villages to meet fishermen. “I would ask people questions, if they had any stories about sharks to tell me. If not, my father or grandfather would have had tales of sharks caught in the fjord or in the estuary,” he recalls.

After living a dream while diving with Cousteau’s team in 1999, Jeffrey Galant co-piloted his first shark-watching expeditions off the coast of Halifax and in Saguenay. For this first great Canadian, an observation cage is being made at the Paul Rousseau Vocational Training Center.

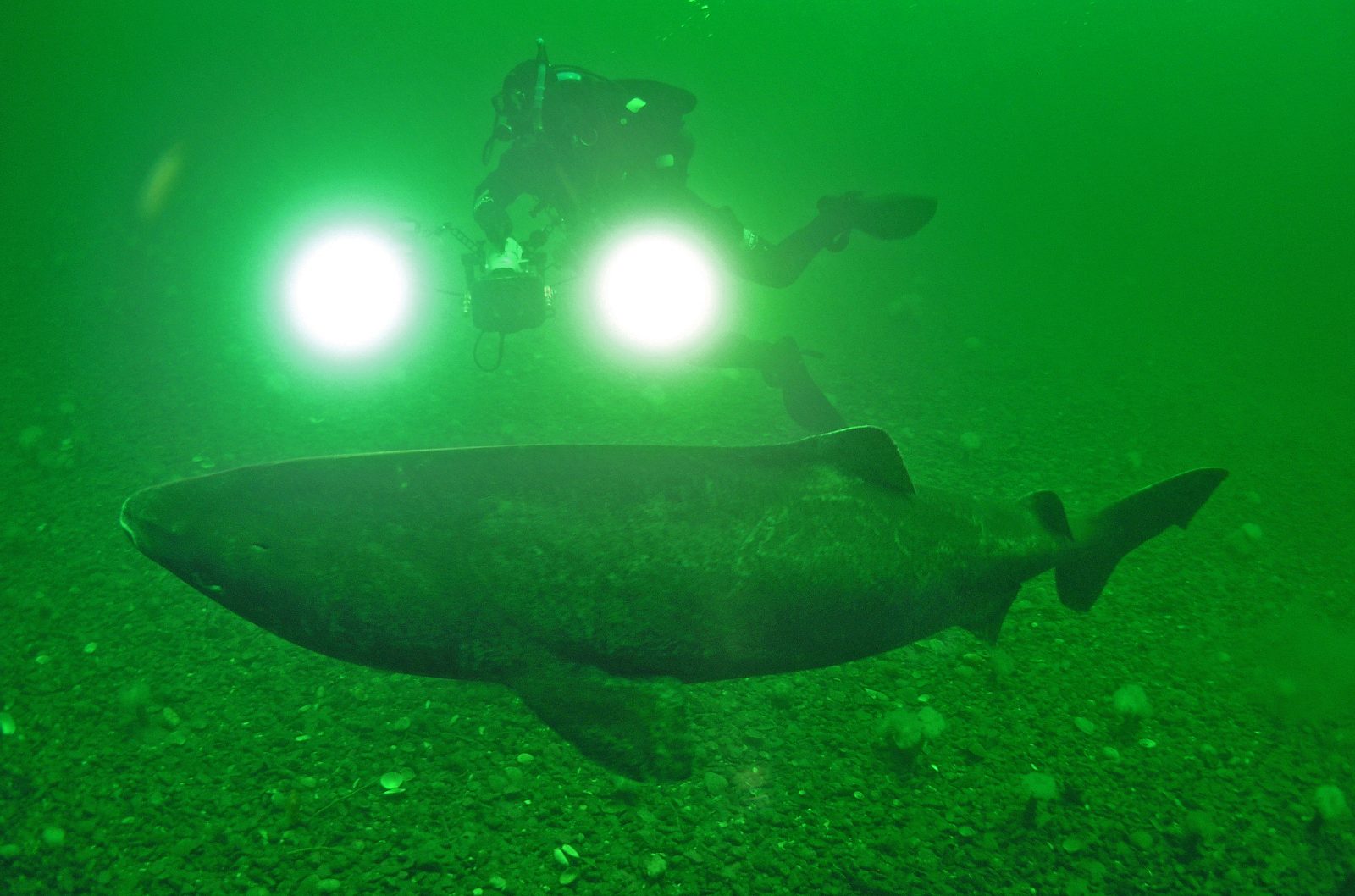

“In Nova Scotia, we saw blue sharks. In Sagueni we organized winter expeditions in difficult conditions. What we were trying to do was the first: meet a Greenland shark under the ice. We place bait stations at several depths to gradually attract him to the cage,” Gallant explains. .

In 2003, citizens contacted Galant to inform him that sharks had been seen in a bay near Bay Como. The next day, the researcher landed on the coast of Cote Nord. “From the first dive, I encountered a woman who was nearly four metres. It was a Greenland shark. All the weight in the world had just come off my shoulders. We had been searching for several years. Finally, we had our shark, but in completely unexpected circumstances. The water was relatively warm. It was on the surface. No cage or bait needed. We were jumping at the end of the pier and the sharks were there,” explains the man who carried out the first sign of a shark in Greenland by placing a transmitter there.

These unusual encounters lasted for eight years, but stopped abruptly in 2011. “We dived in without wondering if we’d ever see a shark, but how many. It’s still the only place in the world where there have been predictable encounters. There seems to be A cycle in which sharks come and then disappear. It is believed to be linked to the movements of their prey. We haven’t been able to put our finger on it yet, but we now have a very good treatment of the environmental conditions that the shark will tolerate. We have made many discoveries and published many scientific articles on the subject.”

big projects

To conduct his research, Jeffrey Gallant founded St. Lawrence Observatory Share, a non-profit organization that studies sharks in Atlantic Canada and the Arctic Ocean. “We’re kind of like Shark Centraide! We’re interested in the nine species that are in the Gulf of St. Lawrence,” Gallant explains.

At the moment, the observatory is particularly interested in the basking shark as well as the white shark. But since 2020, the group has not been able to launch its boat due to the pandemic. Gallant has used the past few months to redirect the organization’s mission, which is now well-respected in the scientific community. “I started small. At first, we paid for everything from our own pockets. We had few resources and equipment. Gradually, I received help from the company’s partners. Today, we are, if not better equipped than some universities, but we rely heavily on charitable donations.

In Gallant’s view, the observatory today stands at a crossroads. “Either we put a cap on or we redirect our goals and do our best to find new sources of funding. To get grants, you have to create research projects and then sell them. That’s what we are going to start doing now.”

Coinciding with the 20NS The anniversary of the establishment of the organization, the year 2023 will mark the beginning of a new phase for the observatory. “We aim to the highest level possible, through projects that will span several years with concrete expectations, scientific discoveries, significant progress or the conservation and promotion of species. We want to educate the population about the importance of the shark, its role and the importance of protecting it. Shark plays a vital role in preserving ecosystems of the oceans, which in some way are a pantry for billions of people around the world,” explains the observatory’s scientific director, noting that sharks are still threatened by the trade in their fins.

“Even if you don’t like sharks, you have to understand and respect their role and try to protect them, albeit selfishly, because you need them to eat fish. We have to explain that to people, even if they don’t appeal to Quakers as much, because we don’t depend on marine resources for food. People are not familiar with sharks in Quebec, even if there are many of them and for a long time”, adds the person who was elected fellow at the prestigious Explorers Club.

At the request of the media as a specialist when shark attacks occur in the country, Jeffrey Gallant recently decided to create the first Canadian registry on these incidents.

“I searched until the seventeenth century to find the first incident that would have occurred during the New France period. There are 25 events included, some of them involving First Nations. It is really a great job, because it combines history, biology and ethics.”

The father of a five-year-old girl adds: “More and more, what I love about my work is that it is no longer just a science, but a philosophy as well.” I realize that everything I have done in life, my knowledge and experience, completes my scientific side. I will take advantage of everything I have. I get a strange pleasure from it all: to write, but to do so as a scholarly human and North American citizen familiar with its origins and privileges. I find it weird! “

This record will also be published in a book on the subject of Gulf sharks. Besides technical papers, this book will focus on the relationship between humans and sharks. Fishermen have a special relationship with sharks. When I met them, I told them that they were also full-fledged biologists. It’s just that they received different training. There is no biologist on this planet who does the same amount of land as them. They are witnesses to extraordinary things. It’s important knowledge that is underappreciated.”

Inspired by his mentor Cousteau, Galant also aims to launch a television series highlighting the sharks of the bay. “We want to engage the people on the seashore. It’s going to be a human story like it’s about sharks.”

More than a scientist, Jeffrey Gallant sees himself today as a true choreographer who coordinates several areas at the same time. “At the beginning of my career, I was naive and full of energy. Today, I’m more aware of all the legs we’ll get with our projects. All that means in terms of logistics, money and time invested. I really don’t go there blindly. It scares me a bit, But these projects will put sharks on the map. It’s essential. People need to know more about sharks so we can take concrete action to protect them. Because in the end, that’s my goal.”

As he approaches retirement from Cégep, Galant now wishes to pursue his profession full time. “It’s good to stop!” Cousteau dived until the age of 85 and ran his foundation until the age of 87. I hope to do the same. Shark Friend concludes that the best is yet to come.

Faithful to Drummondville

Still associated with Drummondville, where he teaches English at Cégep, Geoffrey Gallant continues to lead his project to rediscover the Saint François River and its watershed. Being particularly interested in the annual migration of the great snow goose, he would like to reveal the secrets of this natural gem.

The idea is for the population to regain possession of this body of water that gave birth to so many communities. At the time, Drummondville would not have been established without the river, but it has lost its importance over time. However, when you put your head under water, you make all kinds of extraordinary discoveries. It is full of life! “

“Subtly charming problem solver. Extreme tv enthusiast. Web scholar. Evil beer expert. Music nerd. Food junkie.”