A vaccine that uses messenger RNA technology, the same one found in some COVID-19 vaccines, but this time against AIDS, has shown promising first results in animals, researchers said.

• Read also: Africa: The fight against HIV slows down due to COVID-19

• Read also: AIDS treatment thanks to Quebec

The vaccine was proven to be safe when administered to macaques, and the risk of infection from exposure was reduced by 79%. However, it calls for improvements before they can be tested in humans.

“Despite nearly four decades of efforts by the global scientific community, finding an effective HIV vaccine remains an elusive goal,” immunologist Anthony Fauci, co-author of the study and a House of Representatives adviser, said in a statement. health crisis.

“This experimental mRNA vaccine combines several features that could overcome the failures of other experimental HIV vaccines, and therefore represents a promising approach,” added the director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAD).

Scientists from this institute conducted this work in collaboration with researchers from the US company Moderna, which is behind one of the most widely used vaccines against COVID-19.

The study was published Thursday in the prestigious journal temper nature.

The vaccine was first tested on mice and then on rhesus macaques. These received multiple stimulant doses over one year. Despite the high doses of the mRNA, the product was well tolerated causing moderate side effects, such as temporary loss of appetite.

in 58NS One week, all macaques developed detectable levels of antibodies.

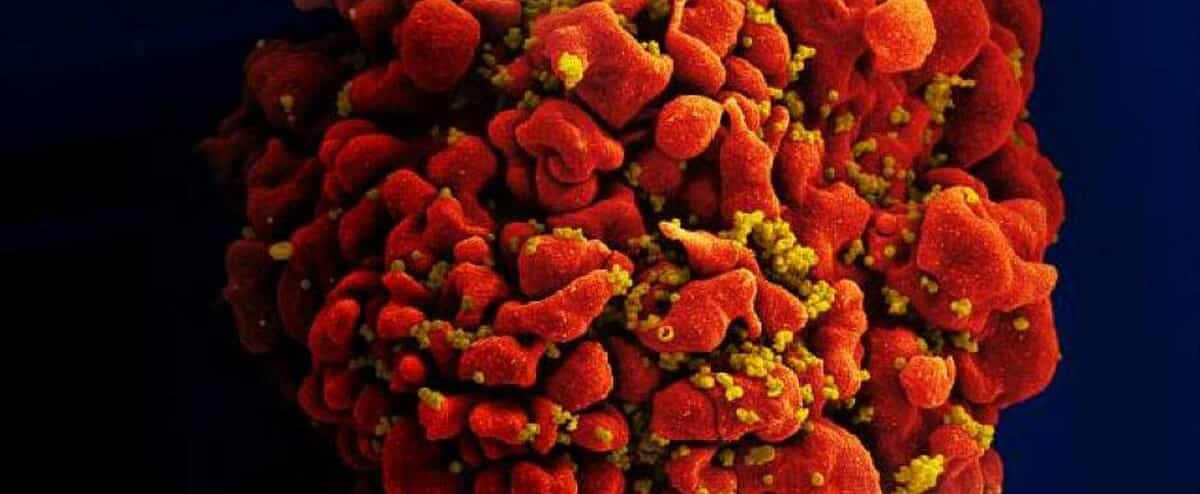

Starting at week 60, the animals were exposed to the virus weekly via the rectal mucosa. Because primates are not susceptible to HIV-1, which infects humans, the researchers used a different but similar virus, simian HIV virus (SHIV).

After 13 weeks, only two of the seven vaccinated macaques were uninfected. But while other unvaccinated macaques fell ill after about three weeks, those who were vaccinated took an average of eight weeks.

“This level of risk reduction can have a significant impact on transmission of the virus,” the study said.

The vaccine works by delivering genetic instructions to the body, which results in the formation of two types of proteins characteristic of the virus. They are then aggregated to form viral pseudopodia (VLPs), mimicking infection in order to provoke an immune system response.

The scientists noted, however, that the levels of obtained antibodies were relatively low, and that a vaccine that would require multiple injections would be difficult to implement in humans.

They therefore wish to improve the quality and quantity of VLPs generated before testing the vaccine in humans.

to see also

“Subtly charming problem solver. Extreme tv enthusiast. Web scholar. Evil beer expert. Music nerd. Food junkie.”